History of the town of Český Krumlov

According to legend, the name Krumlov is derived from the German "Krumme Aue", which may be translated as "crooked meadow". The name comes from the natural topography of the town, specifically from the tightly crooked meander of the Vltava river. The word "Český" simply means Czech, or Bohemian (actually one and the same), as opposed to Moravian or Silesian. In Latin documents it was called Crumlovia or Crumlovium. The town was first mentioned in documents from 1253, where Krumlov was called Chrumbonowe.

The flow of the Vltava River has long been a natural transportation entrance to this region. The area\'s oldest settlement goes back to the Older Stone Age (70,000 - 50,000 B.C.). Mass settlement was noted in the Bronze Age (1,500 B.C.), Celtic settlements in the Younger Iron Age (approx. 400 B.C.) and Slavonic settlement has been dated as from the 6th century A.D. The Slavs were represented by two tribes - Boletice and Doudleby. (Prehistorical settlements of the Český Krumlov region )

In the Early Middle Ages the routes along the Vltava river created the trade routes (see Historical Routes in the Český Krumlov Region). In the 9th century the area was probably owned by the noble Czech family of Slavníkovci, who were slaughtered by the rival family of Přemyslovci in 995. This area then became their property. In accordance with the principles of internal colonization and bestowing of sovereign domains in fief to members of a sovereign dynasty, this domain was thus given by the ruling family of Přemyslovci to one of their own lines - The Witigonen in Czech known as the Vítkovci.

In the Early Middle Ages the routes along the Vltava river created the trade routes (see Historical Routes in the Český Krumlov Region). In the 9th century the area was probably owned by the noble Czech family of Slavníkovci, who were slaughtered by the rival family of Přemyslovci in 995. This area then became their property. In accordance with the principles of internal colonization and bestowing of sovereign domains in fief to members of a sovereign dynasty, this domain was thus given by the ruling family of Přemyslovci to one of their own lines - The Witigonen in Czech known as the Vítkovci.

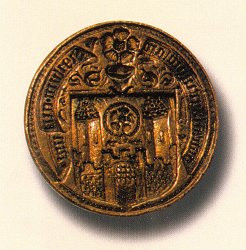

According to the legend, the family of Witigonen has its origins in Ancient Rome. The family was related to the Roman Ursini family, who is said to have resided on the mountain "Mons Rosarum" near the city of Rome. After Rome was plundered by the hordes of the Visigoth leader Totila in 546, the family left Rome and one of its members named Vítek (in German, Witigon) travelled together with his wife and child up to the north, passed the Donau river and settled in Southern Bohemia. He started a new family there and gradually acquired extensive domains, which he gave to his five sons before his death. Each son received a coat-of-arms with a five-petalled rose, the color of which symbolized each particular dominion.

So much for legend - historical reality offers us some slight variations. Vítek did not come to South Bohemia in the 6th but the 12th century, and he did not come from the Italian family of Ursini but from the family line of a Czech Princess of the Přemyslovci. In 1173 Vítek of Prčice was mentioned as an envoy to the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa, and in 1179 he apparently settled in Southern Bohemia. The fact that his domains were not liable to the so-called law of escheat indicates his strong influence, as his property did not have to return to the hands of the family of Přemysl. Vítek could freely dispose of his properties and therefore gave it to his four sons - Jindřich of Hradec; Vítek II senior, predecessor of the Lords of Krumlov; Vítek III junior, founder of the family of Rosenberg; and Vítek IV. It is likely that the then newly founded residences Nové Hrady (New Castles), Rožmberk (Rosenberg), Třeboň and Krumlov fell into the rank of domains of the Vítek family, while Krumlov would have been their fourth castle in the rank. This historically important moment is rendered in the painting "Division of the Roses", which can be viewed in the sightseeing tour at the Český Krumlov castle.

In 1251 the Bohemian King Přemysl Otakar II gained Austrian lands through marriage to Anna Maria of Bamberg. Přemysl Otakar II, with his well-thought out colonization policy, tried to populate the sporadically settled Šumava region in the Czech-Austrian borderland and this way integrate his domains in Bohemia with his newly gained territories in Austria. His efforts in this sphere, however, had its consequences in territories ruled by the sovereign family of Vítkovci, which resulted in particular centres of conflicts with the most powerful aristocratic family in the country. Conflicts had their origins for example in the foundation of the royal town České Budějovice or the Cistercian Monastery Zlatá Koruna (Golden crown), both founded by King Přemysl Otakar II in 1263. Zlatá Koruna was supposed to restrain the influence of the Rosenberg monastery in Vyšší Brod, founded by Peter Wok von Rosenberg in 1259. Frequent disagreements and armed clashes between Přemysl Otakar II and members of the particular branches of the Vítkovec family eventually weakened the power of the Bohemian King.

The town name was first mentioned in a letter of Duke Otokar Štýrský in 1253. The town was established essentially in two stages. The first part was built spontaneously below the Krumlov castle, called Latrán and settled mostly by people who had some administrative connection with the castle. The name and foundation of this part of town is shrouded in legend as well - the castle and town were allegedly built in a place where the Vítkovci overcame a nest of bandits that had been kidnapping and thieving. To the memory of the villain´s hiding place it was called Latrán (Tales and Legends of Český Krumlov). The reality is, however, more prosaic - latus in latin means lateral, side part and residences below the castle were given this name.

The second part of the town was founded as a typical settlement on a "green meadow", i.e. in a place where no previous settlement had been. The town subsequently took shape as a typical colonisation ground plan with a quadratic square in the centre with streets from its corners leading to the town walls. This part of the town and its first Magistrate Šipota were first mentioned in 1274. Since the very beginning of the town both Czech and German nationalities were represented, occasionally even Italian.

In 1302 the Krumlovian branch of the Vítkovci died out, and according to the law of escheat their domains should have passed to the king. At that time the Krumlovian estates consisted of a relatively extensive network of castles and smaller subject towns which were sources of numerous incomes for aristocracy. A member of another powerful branch of the Vítkovec family, Jindřich von Rosenberg, asked the king Václav II (Wenceslav II) to override the law of escheat and vest the Krumlovian estates to The Rosenbergs. They later made Krumlov the main residence of their family.

During the rule of the Rosenberg family, the town as well as the castle flourished. Crafts and trade developed, elaborate homes were built, and the town was endowed with various privileges such as the right to mill, brew beer, hold markets, etc. Meat shops and breweries were built, and twice a year there was a fair. In 1376 there were 96 houses in the town.

Peter I von Rosenberg was the sovereign responsible for giving the town its original 14th century appearance. He was brought up in the Cistercian Monastery in Vyšší Brod, and this upbringing had a strong influence on his personality. Under his rule the Rosenberg estates flourished. Peter became first man of the politics of the day and at the same time the richest aristocrat in the country. He founded the St. Vitus Church in Český Krumlov, the hospital by the church of St. Jošt (St. Jošt Church in Český Krumlov) in Latrán, he invited the orders of Claris and Franciscans and had the Chapel of St. George built in the castle. In 1334, on request from King Jan Lucemburský he invited the Jews to the town. Jews were given a special street in the town and in the functions of chamberlains they were especially responsible for the administration of Rosenbergs´ finances. Peter tried to gain a glory equal to the royal court, even marrying the widow of King Václav III (Wenceslas III), Viola Těšínská. Peter´s sons were engaged in royal services; his oldest son Jindřich died in 1346 at the side of Jan Lucemburský in the battle of the Hundred Years´ War at Kreščak.

Peter I von Rosenberg was the sovereign responsible for giving the town its original 14th century appearance. He was brought up in the Cistercian Monastery in Vyšší Brod, and this upbringing had a strong influence on his personality. Under his rule the Rosenberg estates flourished. Peter became first man of the politics of the day and at the same time the richest aristocrat in the country. He founded the St. Vitus Church in Český Krumlov, the hospital by the church of St. Jošt (St. Jošt Church in Český Krumlov) in Latrán, he invited the orders of Claris and Franciscans and had the Chapel of St. George built in the castle. In 1334, on request from King Jan Lucemburský he invited the Jews to the town. Jews were given a special street in the town and in the functions of chamberlains they were especially responsible for the administration of Rosenbergs´ finances. Peter tried to gain a glory equal to the royal court, even marrying the widow of King Václav III (Wenceslas III), Viola Těšínská. Peter´s sons were engaged in royal services; his oldest son Jindřich died in 1346 at the side of Jan Lucemburský in the battle of the Hundred Years´ War at Kreščak.

The town´s later fifteenth century appearance was given especially by Ulrich II. von Rosenberg. Under his rule, the territory was considerably enlarged, due especially to his clever policy during the Hussite Wars. At the beginning Ulrich supported the Hussite movement, especially in matters of the speculation of church properties. During this time he enriched himself with territories formerly owned by the Cistercian Monastery Zlatá Koruna or Milevsko. After the Hussite disturbances calmed down, he reverted back to the side of the Catholic church and his court in Krumlov became a refuge for Catholic intelligence and artists expelled from Prague. His court thus became a political centre and a bastion of support for the Pope´s process of recatholisation, and at the same time he associated personalities which were gradually accepting ideas of Humanism and Renaissance in the Czech environment.

|

|

In 1420s the method of town administration was modified - the mayor was placed at the head of twelve town councillors who made up a town council. Each town councillor was a mayor for one month and then replaced by another. Besides the mayor and town councillors there was another important person, a town magistrate, who held executive (police) and judical power. Together with the town\'s "great" council board there was also so-called small board whose members were called aldermen. The community of Latrán had its own magistrate and its own representatives in the town board. The town was administered only by the wealthy townspeople such as butchers, maltmasters and drapers. Poorer citizens usually did not have access to the town council board. Councillors had to be approved by the Rosenberg´s lordship.

In the last third of the 15th century Český Krumlov was granted permission to hold weekly and annual markets. The markets were held regularly every Monday while the annual markets always began on the Sunday before St. Havel\'s Day and lasted 8 days. Gradually the town was allowed to hold four annual markets, plus a horse and cattle market. Krumlovians traded with Bohemian as well as Upper Austrian towns. Silver mining began to be supported by the lordship and council board, and Krumlov was considered a free upper town (see History of Mining in Český Krumlov) for a certain period of time.

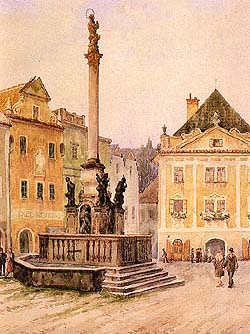

In the 16th century the town was ruled by the last Rosenbergs who considerably influenced the present appearance of the town and its surroundings. The Renaissance magnate Wilhelm von Rosenberg, the most considerable aristocratic personality of the politics and culture of that time, especially initiated reconstructions of townhouses as well as the castle into Renaissance style. On 14th August 1555 Wilhelm joined the two parts of town which had been up to then seperate, Latrán and the Old town, to prevent litigations concerning particular privileges. Before the town´s unification, Latrán had been an individual administrative unit and its dwellers often disputed with those living in the other parts, especially for the privilege to brew white wheat beer, which was very popular and thus a very profitable product. Further problems had been caused by support payments for parish, the church, bridges, the local shepherd and the messenger.

Peter Wok von Rosenberg, the last member of the family, was forced by debts to sell Krumlov to Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg in 1601, who placed his illegitimate son Don Julius there for a short period of time. In 1611 the town faced the heavy assault of the Passau army, during the Thirty Years\' War it was occupied by the Emperor´s army, and in 1648 it was invaded by the Swedish army. The Thirty Years´ War brought a new lordship to the town; the Emperor Ferdinand II of Habsburg vested the town to the Styrian family of Eggenberg in 1622 in return for their financial suppor during the war. Afterwards three generations of the Eggenbergs held Český Krumlov. Only the third-generation personality Johann Christian I. von Eggenberg influenced the town and castle´s appearance by grand construction works and rich cultural and social events.

The family of Eggenbergs died out at the beginning of the 18th century and in 1719 their heirs the Schwarzenbergs came to Krumlov. Under the rule of Joseph Adam zu Schwarzenberg, Český Krumlov overcame the imaginary borders of parochialism for the third time, and with its high level of architecture and cultural and social events reached the level of the leading aristocratic residences in Central Europe. The aristocratic court and standard of living followed the example set by the Emperor´s residence in Vienna. In the 19th century Český Krumlov lost its character of an aristocratic residence; thanks to this it kept its Renaissance-Baroque character. Later constructions were not significant.

The family of Eggenbergs died out at the beginning of the 18th century and in 1719 their heirs the Schwarzenbergs came to Krumlov. Under the rule of Joseph Adam zu Schwarzenberg, Český Krumlov overcame the imaginary borders of parochialism for the third time, and with its high level of architecture and cultural and social events reached the level of the leading aristocratic residences in Central Europe. The aristocratic court and standard of living followed the example set by the Emperor´s residence in Vienna. In the 19th century Český Krumlov lost its character of an aristocratic residence; thanks to this it kept its Renaissance-Baroque character. Later constructions were not significant.

In the mid 19th century the population of the town reached 5,000 inhabitants. A battalion of infantrymen was accommodated there, two comprehensive shools were built, a school of music as well as a so-called work school where children whose parents had died or didn\'t take care of them were placed. In the town were two breweries (princely and municipal), two paper mills, three mills, a flax spinning mill, and a factory for cloth. In the 19th century the architecture of the town also changed its appearance. The town walls were demolished as were all but one of the town gates, Budějovická (see History of Gates and Fortifications in Český Krumlov). At the end of the 19th century the graphite mines were opened by the castle garden, and a factory for listels and frames as well as a new paper mill in Větřní began operation. (Economic History of Český Krumlov)

As early as the 19th century, nationality-based problems sometimes broke out between the Czech and German population. After the Declaration of the Czechoslovakian Republic in October 28, 1918, the German population responded with the Declaration of an Independent Šumava Province

|

|

Böhmerwaldgau which was to become part of a newly constituted Austria. This movement was suppressed by the Czech army and on the 28th of November the region was occupied by Czech forces. By order of the Ministry of the Interior, from 30th April 1920 the town was renamed from Krumau to Český Krumlov, a name which had already been used in 1439. During World War II there were neither any significant battles in Český Krumlov nor bombing. Krumlov was liberated in 1945 by the American army and the German population was expelled.

|

|

|

|

Since the mid 1960\'s, special care has been devoted to the preservation of the historical merits of Český Krumlov; the town was included in 1992 onto UNESCO\'s List of World Cultural and Natural Heritage.

(zf)

Other information:

Timeline

Click-sensitive map of Český Krumlov